What Is /Dev/Null in Linux

Linux treats everything as a file, be it a driver or a device. The /dev directory is used to store all the physical and virtual devices. If you worked with disk partitioning, you may have seen the /dev directory in use. For example: /dev/sda, /dev/sdb1, etc.

Each of the special virtual devices come with unique properties. For example, reading from /dev/zero returns the ASCII NUL characters. Some of the popular virtual devices include:

- /dev/null

- /dev/zero

- /dev/random

- /dev/urandom

The /dev/null is a null device that discards any data that is written to it. However, it reports back that the write operation is successful. In UNIX terminology, this null device is also referred to as the bit bucket or black hole.

Using /Dev/Null in Linux

Properties of /Dev/Null

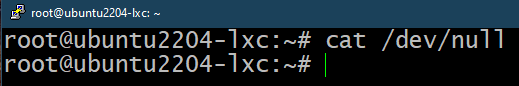

When trying to read from the /dev/null, it returns an EOF character:

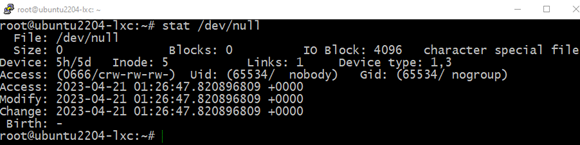

Despite its unique features, /dev/null is a valid file. We can verify it using the following command:

Basic Usage

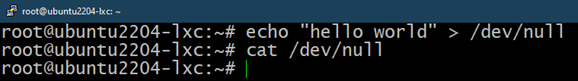

Anything that is written to /dev/null vanishes for good. The following example demonstrates this property:

$ cat /dev/null

Here, we redirect the STDOUT of the echo command to the /dev/null. Using the cat command, we read the content of the /dev/null.

Since /dev/null doesn’t store any data, there’s nothing in the output of the cat command.

Redirecting the Command Outputs to /Dev/Null

Need to run a command without dealing with its output? We can redirect the data to the /dev/null to discard safely. To implement this technique, it requires prior knowledge of file descriptors: STDIN, STDOUT, and STDERR.

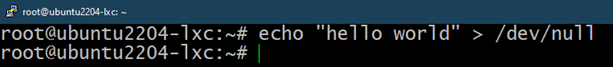

Example 1:

Check out the first example:

Here, we redirect the STDOUT of the echo command to /dev/null. That’s why it won’t produce any output in the console screen.

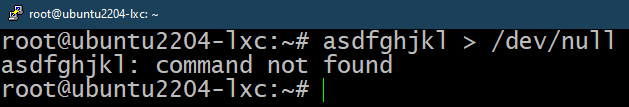

Example 2:

Check out the next example:

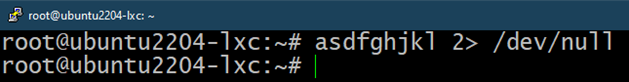

Here, the asdfghjkl command doesn’t exist. So, Bash produces an error. However, the error message didn’t get flushed to /dev/null. It’s because the error message is stored in STDERR. So, we need to specify the STDERR (2) redirection as well. Here’s the updated command:

Example 3:

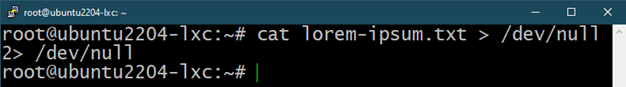

What if we want to redirect both STDOUT and STDERR to /dev/null? The command structure would look like this:

While this structure is completely valid, it’s verbose and redundant. There’s a way to shorten the structure dramatically: redirecting STDERR to STDOUT first, then redirecting STDOUT to /dev/null.

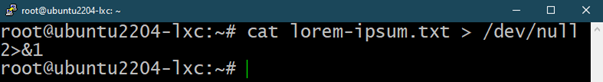

Check out the updated command:

Here, STDOUT is redirected to /dev/null. Then, we redirect the STDERR (2) to STDOUT (1). The “&1” describes to the shell that the destination is a file descriptor, not a file name.

Now, the command is more efficient to implement.

Conclusion

We learned about /dev/null, the null device in Linux. We also demonstrated how it operates using various examples. These techniques are widely used in shell scripting.

Interested in learning more? Check out the Bash programming sub-category that contains numerous guides on various concepts of Bash scripting.

Happy computing!