For years, the Bash shell [1] has been an integral part of many Linux distributions. In the beginning, Bash was chosen as the official GNU shell because it was well-known, quite stable, and offered a decent set of features.

Today the situation is somewhat different — Bash is still present everywhere as a software package but has been replaced by alternatives in the standard installation. These include, for example, Debian Almquist shell (Dash) [2] (for Debian GNU/Linux) or Zsh [3] (for GRML [5]). In the well-known distributions Ubuntu, Fedora, Arch Linux, and Linux Mint, Bash has so far remained the standard shell.

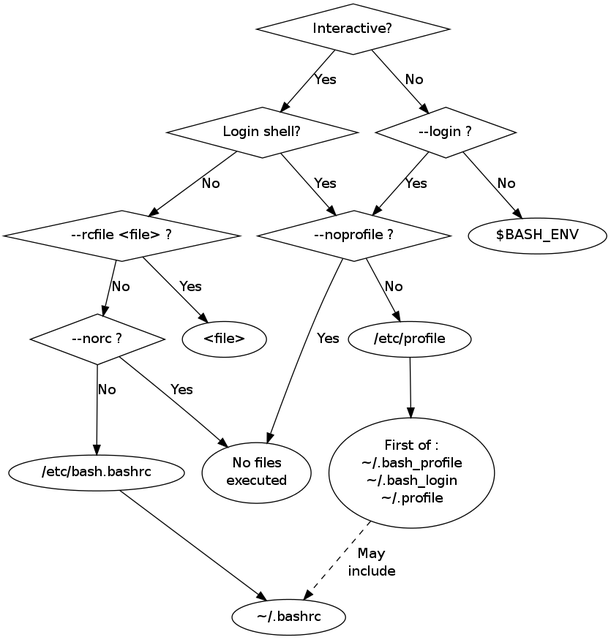

It is quite helpful to understand Bash startup and to know how to configure this properly. This includes the customization of your shell environment, for example, setting the $PATH variable, adjusting the look of the shell prompt, and creating aliases. Also, we will have a look at the two files .bashrc and .bash_profile that are read on startup. The corresponding knowledge is tested in Exam 1 of the Linux Professional Institute Certification [4].

Comparing an Interactive Login and Non-interactive batch Shell

In general, a shell has two modes of operation. It can run as an interactive login shell and as a non-interactive batch shell. The mode of operation defines the Bash startup and which configuration files are read [7]. The mode of operation can be differentiated as follows [6] — interactive login shell, interactive non-login-shell, non-interactive login shell, and non-interactive (batch) non-login shell.

To put it simply, an interactive shell reads and writes to a user’s terminal. In contrast, a non-interactive shell is not associated with a terminal, like when executing a batch shell script. An interactive shell can be either login or a non-login shell.

Interactive Login shell

This mode refers to logging into your computer on a local machine using a terminal that ranges from tty1 to tty4 (depends on your installation — there may be more or less terminals). Also, this mode covers remotely logging into a computer, for example, via a Secure Shell (ssh) as follows:

$ ssh user@remote-system remote-command

The first command connects to the remote system and opens an interactive shell only. In contrast, the second command connects to the remote system, executes the given command in a non-interactive login shell, and terminates the ssh connection. The example below shows this in more detail:

user@localhost's password:

11:58:49 up 23 days, 11:41, 6 users, load average: 0,10, 0,14, 0,20

$

In order to find out if you are logged into your computer using a login shell, type the following echo command in your terminal:

-bash

$

For a login shell, the output starts with a “-” followed by the name of the shell, which results in “-bash” in our case. For a non-login shell, the output is just the name of the shell. The example below shows this for the two commands echo $0, and uptime is given to ssh as a string parameter:

user@localhost's password:

bash

11:58:49 up 23 days, 11:41, 6 users, load average: 0,10, 0,14, 0,20

$

As an alternative, use the built-in shopt command [8] as follows:

login_shell off

$

For a non-login shell, the command returns “off”, and for a login shell, “on”.

Regarding the configuration for this type of shell, three files are taken into account. These are /etc/profile, ~/.profile, and ~/.bash_profile. See below for a detailed description of these files.

Interactive Non-login shell

This mode describes opening a new terminal, for example, xterm or Gnome Terminal, and executing a shell in it. In this mode, the two files /etc/bashrc and ~/.bashrc are read. See below for a detailed description of these files.

Non-interactive Non-login shell

This mode is in use when executing a shell script. The shell script runs in its own subshell. It is classified as non-interactive unless it asks for user input. The shell only opens to execute the script and closes it immediately once the script has terminated.

Non-interactive Login shell

This mode covers logging into a computer from a remote, for example, via Secure Shell (ssh). The shell script local-script.sh is run locally, first, and its output is used as the input of ssh.

Starting ssh without any further command starts a login shell on the remote system. In case the input device (stdin) of the ssh is not terminal, ssh starts a non-interactive shell and interprets the output of the script as commands to be executed on the remote system. The the example below runs the uptime command on the remote system:

Pseudo-terminal will not be allocated because stdin is not a terminal.

frank@localhost's password:

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

You have new mail.

11:58:49 up 23 days, 11:41, 6 users, load average: 0,10, 0,14, 0,20

$

Interestingly, ssh complains about stdin not being a terminal and shows the message of the day (motd) that is stored in the global configuration file /etc/motd. In order to shorten the terminal output, add the “sh” option as a parameter of the ssh command, as shown below. The result is that a shell is opened first, and the two commands are run without displaying the motd, first.

frank@localhost's password:

12:03:39 up 23 days, 11:46, 6 users, load average: 0,07, 0,09, 0,16

$$

Next, we will have a look at the different configuration files for Bash.

Bash Startup Files

The different Bash modes define which configuration files are read on startup:

- interactive login shell

- /etc/profile: if it exists, it runs the commands listed in the file.

- ~/.bash_profile, ~/.bash_login, and ~/.profile (in that order). It executes the commands from the first readable file found from the list. Each individual user can have their own set of these files.

- interactive non-login shell

- /etc/bash.bashrc: global Bash configuration. It executes the commands if that file exists, and it is readable. Only available in Debian GNU/Linux, Ubuntu, and Arch Linux.

- ~/.bashrc: local Bash configuration. It executes the commands if that file exists, and it is readable.

It may be helpful to see this as a graph. During the research, we found the picture below, which we like very much [9].

image: config-path.png

text: Evaluation process for Bash configuration

The different configuration files explained

For the files explained below, there is no general ruleset on which option to store in which file (except for global options vs. local options). Furthermore, the order the configuration files are read is designed with flexibility in mind so that a change of the shell you use ensures that you can still use your Linux system. That’s why several files are in use that configures the same thing.

/etc/profile

This file is used by the Bourne shell (sh) as well as Bourne compatible shells like Bash, Ash, and Ksh. It contains the default entries for the environment variables for all users that login interactively. For example, this influences the $PATH and the prompt design for regular users as well the user named “root”. The example below shows a part of /etc/profile from Debian GNU/Linux.

# Common directories to executables for all users

PATH="/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin"

# Test for root user to add for system administration programs

if [ "`id -u`" -eq 0 ]; then

PATH="/usr/local/sbin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:$PATH"

else

PATH="/usr/local/games:/usr/games:$PATH"

fi

export PATH

}

setuserpath()

# PS1 is the primary command prompt string

if [ "$PS1" ]; then

if [ "$BASH" ] && [ "$BASH" != "/bin/sh" ]; then

# The file bash.bashrc already sets the default PS1.

# PS1='\h:\w\$ '

if [ -f /etc/bash.bashrc ]; then

. /etc/bash.bashrc

fi

else

if [ "`id -u`" -eq 0 ]; then

PS1='# '

else

PS1='$ '

fi

fi

fi

Further configuration files can be saved in the directory /etc/profile.d. They are sourced into the Bash configuration as soon as /etc/profile is read.

~/.bash_profile

This local configuration file is read and executed when Bash is invoked as an interactive login shell. It contains commands that should run only once, such as customizing the $PATH environment variable.

It is quite common to fill ~/.bash_profile just with lines like below that source the .bashrc file. This means each time you log in to the terminal, the contents of your local Bash configuration is read.

. ~/.bashrc

fi

If the file ~/.bash_profile exists, then Bash will skip reading from ~/.bash_login (or ~/.profile).

~/.bash_login

The two files ~/.bash_profile and ~/.bash_login are analogous.

~/.profile

Most Linux distributions are using this file instead of ~/.bash_profile. It is used to locate the local file .bashrc and to extend the $PATH variable.

if [ -n "$BASH_VERSION" ]; then

# include .bashrc if it exists

if [ -f "$HOME/.bashrc" ]; then

. "$HOME/.bashrc"

fi

fi

# set PATH so it includes user's private bin if it exists

if [ -d "$HOME/bin" ] ; then

PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

fi

In general, ~/.profile is read by all shells. If either ~/.bash_profile or ~/.bash_login exists, Bash will not read this file.

/etc/bash.bashrc and ~/.bashrc

This file contains the Bash configuration and handles local aliases, history limits stored in .bash_history (see below), and Bash completion.

# See bash(1) for more options

HISTCONTROL=ignoreboth

# append to the history file, don't overwrite it

shopt -s histappend

# for setting history length, see HISTSIZE and HISTFILESIZE in bash(1)

HISTSIZE=1000

HISTFILESIZE=2000

What to configure in which file

As you have learned so far, there is not a single file but a group of files to configure Bash. These files just exist for historical reasons — especially the way the different shells evolved and borrowed useful features from each other. Also, there are no strict rules known that

define which file is meant to keep a certain piece of the setup. These are the recommendations we have for you (based on TLDP [10]):

- All settings that you want to apply to all your users’ environments should be in /etc/profile.

- All global aliases and functions should be stored in /etc/bashrc.

- The file ~/.bash_profile is the preferred configuration file for configuring user environments individually. In this file, users can add extra configuration options or change default settings.

- All local aliases and functions should be stored in ~/.bashrc.

Also, keep in mind that Linux is designed to be very flexible: if any of the startup files named above is not present on your system, you can create it.

Links and References

- [1] GNU Bash, https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/

- [2] Debian Almquist shell (Dash), http://gondor.apana.org.au/~herbert/dash/

- [3] Zsh, https://www.zsh.org/

- [4] Linux Professional Institute Certification (LPIC), Level 1, https://www.lpice.eu/en/our-certifications/lpic-1

- [5] GRML, https://grml.org/

- [6] Differentiate Interactive login and non-interactive non-login shell, AskUbuntu, https://askubuntu.com/questions/879364/differentiate-interactive-login-and-non-interactive-non-login-shell

- [7] Bash Startup Files, https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/html_node/Bash-Startup-Files.html#Bash-Startup-Files

- [8] The Shopt Builtin, https://www.gnu.org/software/bash/manual/html_node/The-Shopt-Builtin.html

- [9] Unix Introduction — Bash Startup Files Loading Order, https://medium.com/@youngstone89/unix-introduction-bash-startup-files-loading-order-562543ac12e9

- [10] The Linux Documentation Project (TLDP), https://tldp.org/LDP/Bash-Beginners-Guide/html/sect_03_01.html

Thank you

The author would like to thank Gerold Rupprecht for his advice while writing this article.